I have been meaning to come back to this post for well over a year and the current scare going on (as of writing), has put me in mind to finally finish it. Unfortunately the time between reading these two books and now writing this post proper has elapsed and I don’t remember the details of these two novels as well as I did when I began writing.

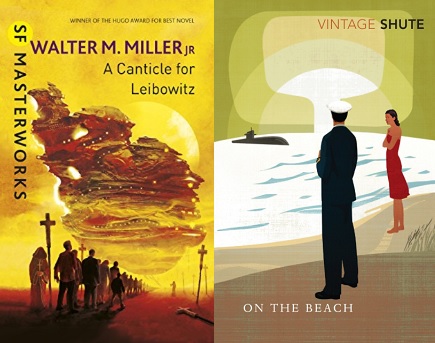

In mid-to-late 2018 read two science fiction books which were both written around the same time and both center around a Nuclear holocaust. My reading them so close together was something of a coincidence but at the time they were written the subject matter was far from uncommon. On The Beach (1957) by Nevil Shute and A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959) by Walter M. Miller Jr were both written well into the Atomic Age and the Cold War. These two realities meant there was a potentially grim future and therefore inspired plenty of equally grim fiction.

Apocalyptic fiction has seen a resurgence in recent history mostly in the form of the “zombie apocalypse” which in its various forms is often caused by a bio-weapon or some other sudden pandemic. The nuclear holocaust science-fiction also inspired the popular Fallout video game series which has since the beginning had a 1950s aesthetic in tribute to the works that inspired these games.

These two works both deal more with the human element than does much similar literature today. They don’t focus on the spectacle of the annihilation of civilisation, as this has already befallen the world before either story begins. However, the outlook for humanity in both is radically different as should be indicated by the title I’ve chosen for this post.

On The Beach is mostly set in Melbourne, Australia after a war has seen mutually destructive nuclear strikes that have wiped out civilisation in the northern hemisphere. A poisonous gas cloud from this exchange is now slowly making its way down with the wind currents and is expected to wipe out all life on earth. As this doom moves steadily south and contact with more and more outposts are lost, the people remaining try to live life as normal. This includes Dwight Towers, the captain of an American Submarine, the USS Scorpion who has put his ship and crew under the command of the Australian Navy. Hope for survival is kindled by a Morse code signal coming from Seattle that may mean humanity in the north has managed to survive.

Something that is immediately hard to believe today is just how calmly the characters are living and going about their lives. Excepting petroleum, there are no great shortages, no riots, no looting and at least until nearer the end — no Bacchic reveling. Essential services are still running as best they can and people are generally just living as though there is a tomorrow despite knowing that there probably isn’t. This isn’t the world and certainly not the Australia that I know today but thinking about how different things were at the time it was written, it is actually believable.

The USS Scorpion is soon sent to investigate the signal and takes along an Australian scientist named John Osborne and a naval officer, Peter Holmes along with them. The submarine is able to stay to carry sufficient supplies and remain submerged, thus protecting the crew from exposure to radiation. In most stories like this, one would expect to find light at the end of the darkness but it is not to be in On The Beach. There is no sign of life found and those sent in protective suits to investigate discover that some power remains and the signals sent are simply an accident of the weather causing a signal key to occasionally be struck by a broken window sash. The situation is truly hopeless and the crew returns to live out what is left of their life on earth.

As death approaches, what is left of the government has organised and issued suicide pills to be taken to avoid a more painful end. There is no real discussion of the morality of this except from Holmes’s wife Mary, who lives with a young daughter and can’t accept what is approaching even as they begin to lose contact with other cities in Australia. Religion does come into it but only as an almost forgotten cultural artifact seen especially through Dwight Tower’s mechanical observance of an Anglican church service. And also through Moira, a would be love interest to the widowed Tower who mutters an ‘Our Father’ before taking her own suicide pill at the very end. The living world then passes away with nothing to hope for in the future.

A Canticle for Leibowitz, begins in what is left of the United States, hundreds of years after a nuclear holocaust known as the “Flame Deluge”. A young novice named Brother Francis of the Order of Leibowitz discovers an ancient fallout shelter and relics of the past within that seem to be from their orders namesake who is soon to be canonised a saint. One of these is a implied to be a circuit diagram but this is unknown to the brothers as technological knowledge of this kind is all but lost. Francis is tasked with taking these relics to the New Rome in the former United States.

The story than moves forward many hundreds of years where the Order of Saint Leibowitz still exists and new city-states and empires are now emerging and long lost technologies are being rediscovered. The relics preserved by the order play a large part in this and orders efforts to preserve this leads to a new scientific age.

The final age the novel covers the late fourth millennium where humans have now mastered intergalactic space travel and have begun colonising new worlds. Humanity has learned little of the previous deluge and a war between the Asian Coalition and Atlantic Confederation will now end life on earth once and for all. The church is prepared for this and has their own intergalactic ships ready to continue Christ’s mission on new worlds. The Order of Saint Leibowitz still survives and the abbot finds himself in conflict with state authorities providing for euthanasia to refugees suffering the effects of radiation. The abbey is soon destroyed by a nuclear attack and the church’s intergalactic mission launches leaving hope for humanity and the church on new worlds.

Both of these novels are very good and well-worth reading though it must be obvious that I found On The Beach a lot more troubling reading. It provoked the same feeling in me that Nineteen Eighty-Four did which was published only eight years earlier. Neither Orwell or Shute were believers as best I can tell which wasn’t unusual for British men of their station anymore than it is now. I feel this disarms them when considering massive human suffering because for them, this life is all there is. This is not to say that this proves them wrong but one cannot help but feel that living is simply pointless with such an outlook and the possibilities for our future they both entertain.

Miller, at the time he wrote A Canticle for Leibowitz, was a very serious Catholic or at least must have spent a lot of time in their company. This is most significant in the heroic Abbot Zerchi’s insistence on the dignity of life even in the face of burning destruction that awaits. For Shute, the pleasures of this world should be enjoyed before comfortably entering oblivion but for Miller, one should live even in suffering in the comfortable hope that this suffering will bring you to paradise. My own religious outlook aside, the problem for Shute is why life should be worth living at all if nothingness awaits? By his standards, the characters in On The Beach would have been just as well served by taking the suicide pills at the beginning of the novel.

Christianity is cultural window dressing for Shute’s characters but it is everything for Miller’s. The very technology used for human destruction only exists because it was preserved by those who saw its higher purpose. The society destroying itself can’t appreciate that. The doctor offering euthanasia in the midst of the destruction can’t even appreciate that those humble brothers may have been right after all. The church uses the technology destroying earth to leave and ultimately preserve life and the society represented in the doctor uses it for destruction right until the end. In Shute’s story, the remaining technology is used as a distraction in the form of a reckless auto race.

Every sliver of hope in On The Beach is quashed and despite the “keep calm and carry on” attitude of what was then an ostensibly British society, the book is still relentlessly depressing. A Canticle for Leibowitz however is always hopeful even in the face of the immense suffering and apparently hopeless situations the characters find themselves in. Both show understanding of human nature though Shute’s is mostly the height of British-American civilisation and Miller’s is the universal state of man without God.

If I believed that Shute’s vision was accurate, I like to believe I would accept it as stoically as Commander Tower did when he dutifully scuttled his ship despite there being no real need to do so. But I have no trouble understanding why Mary Holmes busily went on living and fussing over trivialities in the belief there was a future for her infant daughter. I think that the ability for people to think like this alone is proof that there always is hope.