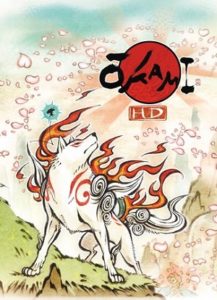

Ōkami was released for the PlayStation 2 in 2006 and is probably best known as the best of the games developed during the brief but prolific existence of Capcom’s Clover Studio. Although not selling very well on release, it was praised mostly for its unique and beautiful cel-shaded visuals as well as gameplay influenced by The Legend of Zelda series. It saw a re-release on the Wii and and a high-definition re-master on the PlayStation 3. I believe it is now available on every major platform including the Nintendo Switch which is the version this review will be based on.

I first played and finished Ōkami in 2008 on the PlayStation 2 just before I left for Japan for the first time. It has been over twelve years since I did and I wanted to see how it held up all these years later.

That Ōkami was inspired by the 3D iterations of The Legend of Zelda series is not controversial. It’s striking similarity with the long anticipated Zelda title released the same year was certainly something to note. The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess was released in late 2006 and the title is related to the Twilight Realm that had taken over much of the land of Hyrule as part of the plot. While inside this realm, the protagonist Link is turned into a wolf. Later on, he gains the ability to transform at will and this becomes essential for progression. Ōkami‘s protagonist is the Shinto sun goddess Amatersasu who has taken the form of a wolf. The game’s title is actually a pun as “ookami” means both God (大神) and wolf (狼) in Japanese. As in Twilight Princess, areas of the land of Nippon (Japan) have been covered in darkness as Amaterasu must restore light to these areas by restoring a spiritual tree in each area. I doubt these similarities are more than coincidences as these themes are legion in Japanese media and Ōkami wears its influence openly.

The influences aren’t just superficial as Ōkami also includes a lot of other similarities. From a fishing mini-game, a small fairy guide (Issun), to magical powers bestowed by divine beings as well as dungeon and puzzle design. It even uses ideas specific to previously released Zelda games such as moments where the protagonist is shrunk to visit a smaller people and even to travel within the inside of a diseased body. There is also a journey under the ocean, dojo training and the cel-shaded design popularised by The Wind Waker.

The pacing is often tedious — especially early on. There is a lot of expository dialogue right through to the end and it is uses a garbled language similar to both Animal Crossing and Star Fox which gets annoying very fast. Cutscenes are frequent and often only to explain the obvious. Notably, when a puzzle or goal is not so obvious, no explanation is forthcoming. It is rare though when exactly what will need to be done is not explicitly laid out.

The most unique element apart from Ōkami‘s art design is the use of the celestial brush. With the assistance of your companion Issun, you are able to stop the action at any time in order to paint on the land as if it were a divine canvas. This is employed liberally in both combat and in order to solve puzzles. As the game progresses, thirteen different techniques are unlocked. All of them are simple swirls, circles or lines as anything more complicated would doubtless of hindered the gameplay. These techniques are fun to use in the environment but just slow down the experience as combat mechanics.

Ōkami‘s combat is arguably the weakest aspect of the game. New enemies are frequently introduced and combat always takes place in a fiery arena. The speed with which you dispatch your foe as well as how much damage you avoid are rated at the end of each encounter. The reward for each battle is money which can be used to buy items and weapons. There is a progression system for certain upgrades called “praise” but this isn’t earned generally from enemy encounters. As money is abundant and there is no real challenge or enjoyment in fighting enemies, these encounters early on become something to avoid as there is little to be gained when they aren’t forced.

The game itself is very easy if your goal is simply to finish it. I got through most of the game without using or even knowing what many items were used for. There are specific strategies for many enemies but most can be overcome by relentlessly attacking them. It was only in the last few hours of the game that I began using many of the combat related items I’d collected from chests hidden through the game.

The boss battles to differ from the general enemies with some clever design and each major boss is unique. This is let down by one in particular which has to be fought three times and this boss also happens to be the lengthiest. The third fight is right at the end where all but the penultimate bosses must be fought again which lazily extends the end game.

I felt the game itself also overstays its welcome. Perhaps if there was less exposition, I wouldn’t have felt this way but on both playthroughs I felt it could have been improved a lot by being truncated.

Ōkami has a very interesting concept and certainly beautiful art design that holds up well today. It is also up there with Muramasa: The Demon Blade in the way it paints the Japanese aesthetic of both nature and culture. This is something I could appreciate all the more as I was to experience the real Nippon shortly after first playing it.

Considering it strictly as a game for entertainment purposes, I feel it will be always divisive. Even though I love most games in the genre, I don’t think it is anywhere near as fun to play as its inspiration. This will be one players either see through to the end and beyond or else abandon forever after a few hours of play. It isn’t bad nor is it overrated, it is just a game that people will either like, love or loathe.

A major difference from the ports and the original is the absence of the song Reset by Ayaka Hirahara in the ending credits. If nothing else, this is worth listening to and it’s a shame it wasn’t present in the later releases.