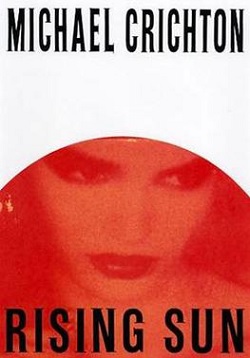

Rising Sun by Michael Crichton, Alfred A. Knopf Inc, January 27th, 1992

Rising Sun by Michael Crichton, Alfred A. Knopf Inc, January 27th, 1992

Rising Sun is a novel written by Michael Crichton while he was still at the height of his literary powers. It was published after Jurassic Park and before Disclosure — the latter of which I have not read.* All three were successful novels that were quickly adapted into successful films.

The subject matter of the novel is rather out of date today and it is best read as a period novel, as the issues of the time now seem rather quaint. The title is both obvious but still clever with three levels of meaning that I could pick out. The obvious being a direct reference to Japan as the land of the rising sun. The next being its position at the time as a major world power that was expected by many to eclipse the economic power of the United States. This features heavily in the plot with the two detectives investigating a murder at the Nakamoto Corporation. The last meaning can be seen in the time much of the story takes place where the detectives are racing against the sunrise to solve the murder. The actual plot goes on three nights though.

Although I’m certainly not very familiar with the genre, the book and film both have elements of classic American detective fiction and film noir. A quick search supports this as it wasn’t lost on critics. The film follows the book as closely as one could hope with the only major changes being the white character Peter Smith becoming the black Webster Smith. This was at a time when race-swapping characters was done less maliciously and absurdly than today. It also actually works as racism is a strong thematic element and the buddy cop dynamic found in the Lethal Weapon series had been well-received by audiences.

Almost thirty years later, things are very different. At the time of publication, the Japanese economy had already begun to decline and the fears of Japanese dominance now seem laughable though Crichton’s observations about American politicians and corporations willingly selling out their nation to foreigners are all too accurate. Nowadays, Japan has been usurped by its unfriendly neighbor China but remains a strong and (more importantly) stable nation. The United States today needs no help from foreigners to commit economic and cultural suicide. Americans could be now forgiven for wishing the Japanese had come to dominate the country.

Crichton’s style in all the novels I’ve read was to have characters explain scientific concepts or some other extended but relevant piece of trivia to another character or characters. He excelled at having things explained in ways that most readers could easily follow and while I’m sure literary pedants found it wanting, I always found these asides fascinating.

In Rising Sun, Crichton has the character John Connor explain different aspects of Japanese culture to the protagonist, Peter Smith. Although some critics seemed determined to have found fault with the novel (and the film) for being anti-Japanese, Connor is sympathetic to the Japanese and I suspect Crichton was too. As I lived in Japan for a decade fifteen years after the novel’s publication, I found these parts of particular interest.

In the film, John Connor is portrayed by Sean Connery and his commentary on the Japanese is far briefer — as is his use of their language. It also seems to have been changed to be more sympathetic to the Japanese though I would maintain that Crichton’s main target is the willingness of Americans to voluntarily sell themselves out and not Japan’s willingness to take advantage of this.

What follows are some of the extended quotes from John Connor which I found interesting and my commentary. As a last aside, I am a bit puzzled as to why Crichton used that name for the character as Terminator 2: Judgement Day was released the year before, is set in the same city and is still a much loved film today. Realistically though, it is a fairly common sort of name so it still works.

On to the commentary.

‘Japanese organizations are actually very slow to respond in a crisis. Their decision-making relies on precedents, and when a situation is unprecedented, people are uncertain how to behave. You remember the faxes? I am sure faxes have been flying back and forth to Nakamoto’s Tokyo headquarters all night. Undoubtedly the company is still trying to decide what to do. A Japanese organization simply cannot move fast in a new situation.’

What is most interesting about this in hindsight is that the Japanese still use fax machines. Indeed, despite their maintaining a strong association with the cutting edge of technology, their society as a whole is still relatively low-tech. Cash is still widely used over electronic transactions — which now seems a very prudent preference. They also famously had a minor crisis when Microsoft announced it was ceasing support for Windows XP when even grandmas had switched to Windows 7 or whatever Apple had available in Western markets.

But the main point about their plodding nature remains true from my personal observations (which is mostly what I’m going on). This is something that quickly becomes irritating to the more independent-minded and has had me comparing them to Tolkien’s Ents who famously managed to lose the patience of the otherwise indecisive Hobbits.

‘Compared to the Japanese, we are incompetent. In Japan, every criminal gets caught. For major crimes, convictions run ninety-nine percent. So any criminal in Japan knows from the outset he is going to get caught. But here, the conviction rate is more like seventeen percent. Not even one in five. So a criminal in the States knows he probably isn’t going to get caught — and if he’s caught, he won’t be convicted, thanks to all his legal safeguards. And you know every study of police effectiveness shows that American detectives either solve the case in the first six hours, or they never solve it at all.’

What I found interesting about this comment is the omission that a man who had Connor’s experience with the Japanese must have known. This of course is the aggressive and highly questionable way the Japanese police operate. I read something of this most recently in Haruki Murakami’s Underground where the Japanese police were after victims of the sarin gas attacks in seeking perpetrators.

The police certainly do get results in Japan but I would put this down to a number of factors outside their general competence. One would be that the Japanese in general, are far more law-abiding than Americans and Westerners which means many major crimes will be ones of passion or opportunity when not a serial killer. These crimes are far easier to solve. They are also much more homogenous and there aren’t many places for criminals to hide. A quote below adds to this.

Most importantly, the percentage of ultimately wrongful convictions would put a big question mark over their conviction rate to say the least.

‘It’s hard for an American to see him clearly,’ Connor said. ‘Because in America, you think a certain amount of error is normal. You expect the plane to be late. You expect the mail to be undelivered. You expect the washing machine to break down. You expect things to go wrong all the time.

‘But Japan is different. Everything works in Japan. In a Tokyo train station, you can stand at a a marked spot on the platform and when the train stops, the doors will open right in front of you. Trains are on time. Bags are not lost. Connections are not missed. Deadlines are met. Things happen as planned. The Japanese are educated, prepared, and motivated. They get things done. There’s no screwing around.’

I think expecting things to not work or break down in the West is somewhat hyperbolic but he’s not wrong in general. I can attest that the buses and trains do run on time and the trains do stop exactly where they’re supposed to. I lived their long enough to experience disruptions but these were exceedingly rare. One involved a typhoon that shutdown the trains in the city I lived, which I think even the Japanese would be forgiving of. I do recall also a bus being late and one passenger repeatedly berating the driver for the extra minute or two he had to wait too. The bus driver was more than gracious in receiving this criticism from my perspective. After all, a bus driver has far less control over traffic than a train driver does.

Contrast this with the years since I returned to Australia and began living in Brisbane. Buses and trains are often late. The railway system is nowhere near as sophisticated or as widely used as in Japan but the lines seem to be shut down every few months and replaced by coaches. I never experienced anything like this while living in a major Japanese city and it does make you wonder about the competence of our own transport services.

Everything else mentioned is more or less true as well. My mail always arrived on time and was never lost. I got things when I was supposed to and society generally ran like clockwork. Living amongst them I did experience more errors and mistakes than the average visitor would but these were still rare. I remember for example a young lady bringing me a coffee and accidently spilling some in the saucer. She turned to get me another with a terrified look on her face until I assured her I was fine with it as it was. The other side of the coin you can interpret from this is the Japanese can be viscously exacting on those unfortunate enough to make mistakes.

‘Remember, Japan has never accepted Freud or Christianity. They’ve never been guilty or embarrassed about sex. No problem with homosexuality, no problem with kinky sex. Just matter-of-fact. Some people like it a certain way, so some people do it that way, what the hell. The Japanese can’t understand why we get so worked up about a straightforward bodily function. They think we’re a little screwed up on the subject of sex. And they have a point.’

This sort of statement I have often heard of the Japanese but this is probably something I most disagree with. If this were true then Japan would have been one of the first to recognise the Unholy Sacrament of Sodom (gay marriage). As of writing, they are behind almost every other Western nation by a number of years — including the notoriously “puritanical” United States. And even then, if it is ever recognised, it will be through constitutional system imposed on them by the United States at the end of the second world war and not their own cultural inclinations.

In other ways, this makes no sense as the United States is (or at least was), the source of most of the world’s pornography. Japan as far as I know still has decency laws regulating it much more strongly than in other nations. Please note that I don’t disagree with this, I am just pointing out it contradicts Connor’s statement.

It is true that the Japanese are a rather perverted race but they aren’t really open about it. Most of this happens behind closed doors in hushes and whispers. The magazines on open display and some of their television might occasionally be a little more shocking but they aren’t upfront as a people. You wouldn’t want to be caught by co-workers let alone your boss, browsing certain magazines in a convenience store or recognised at any house of ill repute. And the average Japanese person is not likely to be nearly so open and accepting about their spouse’s kinks as Connor seems to think.

As for sodomites and trannies (but I repeat myself), the media is a lot more tolerant than the average Japanese person is. If you don’t believe me, try surprising the average Japanese family at dinner with the news that you are one. I’d wager they’d be considerably less comfortable than you think. The truth is, that Japanese are fascinated with perverts much like rural Americans once were with bearded ladies at carnivals. They are otherwise inoffensive oddities that can give some brief entertainment. Much certainly goes on underground but Japanese aren’t big on public displays of perversity and you really wouldn’t notice if you didn’t look for it.

The Westerners that believe as Connor do are more likely spending more time interacting with the more Westernised intellectual class than Japanese in general. These people are a far cry from the average Japanese person.

‘The Japanese are masters of indirect action. It’s their instinctual way to proceed. If someone in Japan is unhappy with you, they never tell you to your face. They tell your friend, your associate, your boss. In such a way that the word gets back. The Japanese have all these ways of indirect communication. That’s why they socialize so much, play so much golf, go drinking in karaoke bars. They need these extra channels of communication because they can’t come out and say what’s on their minds. It’s tremendously inefficient, when you think about it. Wasteful of time and energy and money. But since they cannot confront — because confrontation is almost like death, it makes them sweat and panic — they have no other choice. Japan is the land of the end run. They never go up the middle.

. . .

So behavior that seems sneaky and cowardly to Americans is just standard operating procedure to Japanese. It doesn’t mean anything special. They’re just letting you know that powerful people are displeased.’

I definitely experienced this and I had warning it would happen too. The thing is despite being forewarned, I was still furious every time it did. Note, that almost every time it did happen, it was over a misunderstanding and never (as far as I know), over incompetency or poor performance. And even after knowing, experiencing and understanding their perspective, I consider it cowardly. I see no reason to change my mind.

‘It took me a long time to understand,’ he said, ‘that the Japanese behavior is based on the values of a farm village. You hear a lot about samurai and feudalism, but deep down, the Japanese are farmers. And if you lived in a farm village and you displeased the other villagers, you were banished. And that meant you died, because no other village would take in a troublemaker. So. Displease the group and you die. That’s the way they see it.’

I’ve never heard it put quite this way but it does make sense. This happens to be one of my biggest problems with the Japanese nation. The social ostracism and the inability for the average person to redeem themselves or ever hope to be forgiven leads to a fatalistic mindset that often results in suicide. This also means that the Japanese will do things like covering up or avoid admitting mistakes. They will come into work when clearly too unwell to be there and slow down everyone else in their workplace as a result. All to avoid displeasure. There are good aspects about this but on a higher level, it means there is little charity among the Japanese.

‘Most people who’ve lived in Japan come away with mixed feelings. In many ways the Japanese are wonderful people. They’re hardworking, intelligent, humorous. They had real integrity. They are also the most racist people on the planet. That’s why they’re always accusing everybody else of racism. They’re so prejudiced, they assume everybody else must be, too.

And living in Japan . . . I just got tired, after a while, of the way things worked. I got tired of seeing women move to the other side of the street when they saw me walking toward them at night. I got tired of noticing that the last two seats to be occupied on the subway were the ones on either side of me. I got tired of the airline stewardesses asking Japanese passengers if they minded sitting next to a gaijin, assuming that I couldn’t understand what they were saying because they were speaking Japanese. I got tired of the exclusion, the subtle patronizing, the jokes behind my back. I got tired of being a nigger. I just . . . got tired. I gave up.’

. . .

‘I do. I like them very much. But I’m not Japanese, and they never let me forget it.’

I would agree with everything in the first paragraph. The only time I’ve ever experienced “racism” was in Japan. As I’m a White Australian with British heritage, this didn’t really offend me though I did try to be offended. Many Westerners take a masochistic pleasure in being able to experience racial prejudice and Japan or really anywhere in eastern Asia is the place to experience it if you so desire. I’m not trying to imply that I have any sort of racial privilege, just that I am not really bothered what people think of me. I don’t have any racial or cultural self-esteem issues.

The second part of what Connor said, I did get tired of too. I don’t blame the Japanese for this though. Japan is their country and I was a foreigner in their country. They have no obligations to me. Some things had changed since the novel was written as I can’t remember a time someone crossed the street to avoid me. People did tend to avoid sitting next to me until most seats were taken on the train but it wasn’t all that obvious unless I was looking out for it. There were a few times that I can recall but I wasn’t offended and even remember laughing about them with other Westerners. I think the Japanese had gotten a bit more used to Western foreigners by then and knew we were mostly harmless. Mostly.

Like the fictional Connor, I am quite fond of the Japanese but I know I am not Japanese. I never will be Japanese. A Japanese will also never be an Australian despite what the current year likes to pretend. I would live in Japan again and I wouldn’t mind experiencing the same things Connor describes in doing so either.

I don’t know how familiar Crichton was with Japan but I’d say he did good research if nothing else. The character of Connor comes off as authentic and even decades later, his descriptions of Japanese culture ring true.

*UPDATE (09/06/21): I have since read Disclosure and seen the film adaptation. Similarly to Rising Sun, it is outdated in many ways but also ahead of its time in others. The book was much better than the film. It would be close to impossible to get a book like this published with a mainstream publisher today. The film would never be made.