I only recently learned of the existence of Imaro by the late Charles R. Saunders through the dissident literary circles in which I often spectate, but seldom participate. I immediately sought out the two books pictured above, which as of writing, are the only two easily available. It brought me joy as I had discovered a genuinely talented pulp author, with a unique take on the genre popularised by authors such as Edgar Rice Burroughs, Robert E. Howard and Fritz Leiber. This joy was accompanied by a twofold sorrow as the author passed away in May of 2020, largely unremarked and had I only discovered him a few years earlier, I could have not only purchased all his books directly but perhaps even sent him a message of thanks and appreciation. His passing was at least covered by Morgan Holmes on the Castalia House blog (who also corresponded with him), and he was even given a more fitting headstone with the help of a Kickstarter project a few years ago. It is unfortunate that something else he will no doubt share with Robert E. Howard (and indeed many great authors), is having others profit from his creations long after his death.

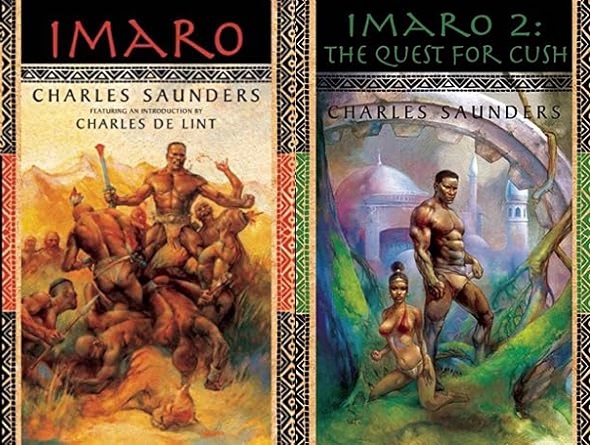

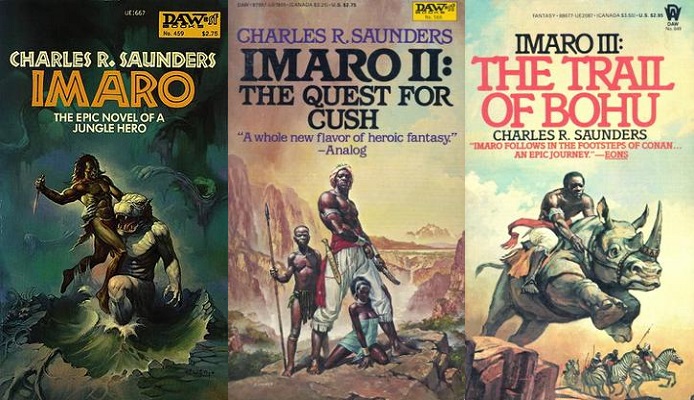

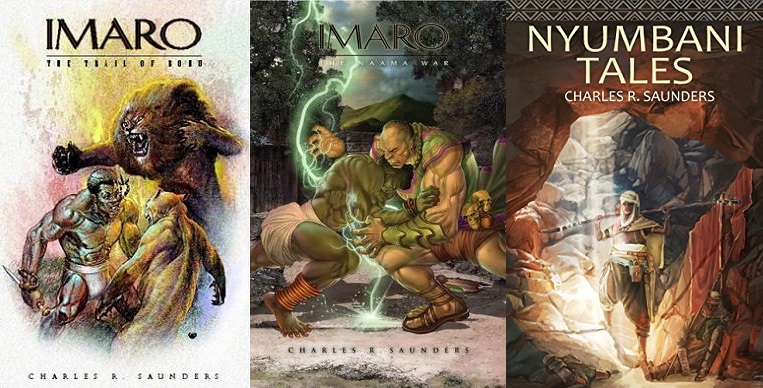

Before proceeding to the review of the two books above, it is worth giving a bit of background to the publishing history which consistent with a lot of pulp works, takes a little more mental energy than the norm to keep track of. The first of his Imaro stories were published in a fanzine called Dark Fantasy most (if not all), were collected together in his first Imaro novel published in 1981 by DAW Books. This was followed by The Quest for Cush (1984) and The Trail of Bohu (1985). The sales were not good enough to continue the series and these original books are now very expensive on the used market; unless you get lucky at a garage sale or a book store that doesn’t check online prices. The series was brought back (due partly to the enthusiasm of an Australian fan who discovered the old paperbacks), which led to the first two books being republished in 2006 and 2007 by Night Shade Books. A similar story with poor sales meant that the third book was not re-published and the already written fourth and final book was not either. These two books from Night Shade are the two I have though there were a number of changes made to these editions including one of the original stories being replaced with a new one due to its eerie similarity with the Rwandan Genocide in 1994. Outside of scarcity, these differences are part of the reason the original DAW publications (and I’m sure the Dark Fantasy magazines), remain collector’s items.

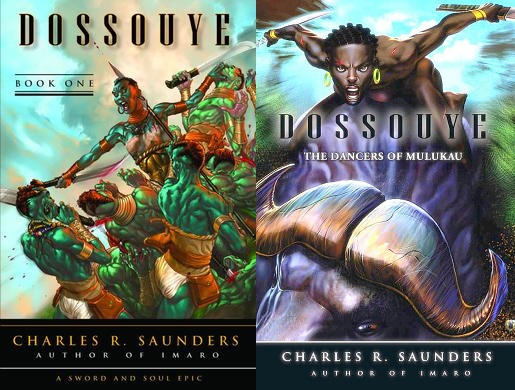

Saunders finally began Sword & Soul Media through Lulu.com to republish the third book in 2009 and also the final book called The Naama War, the same year. He also published other fantasy works including Dossouye (2008) and Dossouye: The Dancers of Mulukau (2012) and finally a short story collection set in Imaro’s world called Nyumbani Tales in 2017: all through the same online storefront. Unfortunately, I’m a few years too late to be able to buy these and they are all now unavailable. Who now owns the rights to Saunders’ oeuvre is unknown as of writing but I, for one, would certainly jump at the opportunity of reading more after getting a taste of Imaro’s world in the first two books.

Although not well-known, there are quite a few articles about Charles Saunders’ work, including many through Castalia House Blog’s Sensor Sweep. Searching the linked site, or any search engine will bring you much of the information above but I offer (I hope), a unique though still very positive perspective below.

Charles Saunders died at the beginning of what was (for a number of reasons), one of mass public insanity. Though this opinion is not widely shared, I’m more confident than not that future generations will see it as I do. One of the manifestations of this insanity (which curiously came up in my last post too), was related to the racial chaos that was sparked by the death of a violent criminal and was officially (and unofficially), encouraged and facilitated by various branches of the United States government. This was also used to further push what is generally known as “diversity and inclusion” (DEI) across virtually all types of media including comics, literary fiction, television, film and video games. This was certainly happening prior but it really accelerated in 2020 and has shown little sign of stopping. Some examples are mediocrities like N.K. Jemisin and Ta-Nehisi Coates being promoted simply for being able to write while black. The more common practice is to take existing intellectual properties and media franchises and make characters gay, black, disabled or a compound of two or more of the ever growing variety of groups seeking special status if not for their sins, then for merely existing.

I didn’t begin writing this intending it to be in any way polemical and the above is written to pay what I believe is the highest compliment I can to Charles R. Saunders. That is simply that he was a genuinely talented writer that deserved the promotion instead given to so many lesser writers. From what I know of his biography, he would more than likely vehemently disagree with the above paragraph and were he alive to do so, I would still buy his books. That his obvious talent was only appreciated by a niche group for most of his life, despite having the correct credentials with regards to race and political views, reveals the malevolence that really is at the heart of the destructive madness rampaging through most forms of popular media. That his books sold poorly despite their quality is beside the point as much lesser writers (including no shortage of European ones), have nonetheless been widely promoted.

Rather than complain about the elements of fantasy he didn’t like including the portrayal of his people, he decided to write his own. He didn’t seek to ravage the work of others from resentment and took the harder but more rewarding path of creating his own. I can even sympathise with how a young Charles Saunders might have felt when he read passages like this within the original Tarzan of the Apes:

THIS IS THE HOUSE OF TARZAN, THE

KILLER OF BEASTS AND MANY BLACK

MEN. DO NOT HARM THE THINGS WHICH

ARE TARZAN’S. TARZAN WATCHES.

TARZAN OF THE APES.

This is merely a sample and there are a lot worse examples than this in almost any early pulp story you pick up. Nonetheless, Saunders didn’t destroy: he created.

It would be easy to directly compare Saunders’ Imaro to Howard’s Conan or Burroughs’s Tarzan and these were certainly influences as well as useful comparisons to promote or describe what to expect from these books. These famous characters have often been copied and these derivatives usually only capture the superficial aspects of each character. Most people who recognise Conan or Tarzan, have little if any knowledge of the original stories; only the images found in popular culture. This is somewhat similar to how Frankenstein’s monster and Dracula have popularly become caricatures of what they really were in the original novels. Imaro is distinguished not just by the African inspired setting of Nyumbani, as he stands apart from these characters in a number of notable ways.

He is certainly strong, fast, determined, grim and a natural warrior as Tarzan and Conan are. Imaro doesn’t become a lone outsider by accident or by leaving his native home; he is so by birth. His mother Katisa was born among the fiercely territorial Ilyassai tribe who live in a savanna called the Tamburure. After finding a lover outside the tribe, she is rejected by her own as is her half-caste son, Imaro. His mother chooses exile on the condition that her son can remain among her tribe which is accepted though Imaro is still despised from youth and grows up in harsher circumstances due to this. Life among the Ilyassai is difficult even for full-bloods and achieving manhood requires young warriors to kill a lion in combat. This tough existence along with Imaro’s natural strength and speed forges him into a powerful warrior.

Despite overcoming these challenges on his path to manhood, Imaro is cheated out of acceptance by malevolent powers exercised through the tribe’s sorcerer Chitendu, who it is discovered holds loyalty to dark forces outside the tribe. He has a special hatred for Imaro and his exiled mother Katisa for reasons that are developed later in the narrative. This all leads to Imaro leaving his unwelcome home and journeying as a wanderer among different regions and peoples as well as encounters with eldritch horrors that are a signature of the sword and sorcery genre.

Quite unlike Conan, Imaro has a clear moral core: even when he is captured by and comes to lead a group of bandits. He holds to the traditions of his tribe which is illustrated amusingly in the second book where he takes exception to a trader beating his ox (ngombe) in the city of Mwenni. This treatment of an animal that his own tribe treats with more care than their own, provokes him to seek to murder the trader and he only prevented by the intervention of his far more worldly companion Pomphis. Imaro isn’t a stupid brute though, he simply has no knowledge of the norms of civilisation which allows things his more savage society does not. A major theme found in Howard’s works then is present, but Imaro learns from these experiences and gradually comes to understand these differences among peoples. He is barely past adolescence when he begins his journey and so is still becoming more aware of the peculiarities among different cultures. He is certainly not an anti-hero.

As befitting pulp, these books are written more as a group of short stories than as chapters of a novel. The major difference between these stories and Conan is that they begin with Imaro’s origins and continue chronologically but it is certainly possible to read one story without having much background to what has gone before. I assume this continues in the final two books which as of writing are unavailable to me. What is encouraging is that the stories I read only improved as the narrative progressed and more of Imaro’s destiny is revealed.

Something else that distinguishes Imaro, is that though he begins a lone traveller, he does not long remain so. He makes friends and even forms a loving relationship with the beautiful Tanisha of the Shikaza tribe. This tribe is known for the beauty of its women and both Imaro and Tanisha become devoted to each other and this certainly contrasts with Conan, whose travels involve many women of very varying virtue. The pygmy Pomphis (mentioned above), also becomes one of Imaro’s companions and often acts as something of an unofficial cultural guide to Nyumbani.

Saunders makes liberal use of Swahili in naming much of his world including it’s name Nyumbani which means “home”. Other races are present as are hints of analogues of other nations of our world. One is the heroic Chang Li who comes from an analogue of China as well as traders of other races which judging by the names are equivalents of Indians, Persians and Arabs. The European races (at least from these first two books), are Atlanteans who once enslaved the people of the Nyumbani before they were defeated and driven out. Imaro encounters a degenerate remnant of them when they capture his beloved Tanisha; intending to sacrifice her to prolong their evil lives. They are called Mizungu which the glossary translates as “those without mercy.” Saunders also helpfully translates these unfamiliar words within the prose and so you aren’t required to repeatedly flip back and forth.

So in writing this, I’ve probably partially addressed the reason why Saunders writing wasn’t given more promotion given his obvious talent, his race and his politics (which I assume are a world apart from my own). The answer seems to be that Imaro is a truly heroic and masculine character. His love interest is feminine and always behaves so — and Saunders seems to have a good understanding of a woman’s mind. He is also on a journey against an unmistakably evil force and so shares some similarity with Howard’s Solomon Kane too. This is not the sort of story the literary infidels want to promote, regardless of who wrote it. I can thankfully only imagine what this would be turned into if it were adapted to television or film. The only good that could come out of Hollywood getting a hold of it would be seeing these original stories being republished and made more widely available.

For now, I enthusiastically recommend anyone who is interested to seek out the two books that remain available as of writing. Saunders writes in engaging and entertaining prose with his unique spin on classic pulp, sword and sorcery with plenty of otherworldly monsters, magic and visceral violence. I’m so into it I’ve ordered the only other book available with an Imaro story which is an anthology of “sword and soul” edited by Saunders and titled Griots. I may not be the intended audience but I certainly enjoy and appreciate what Charles Saunders has done.